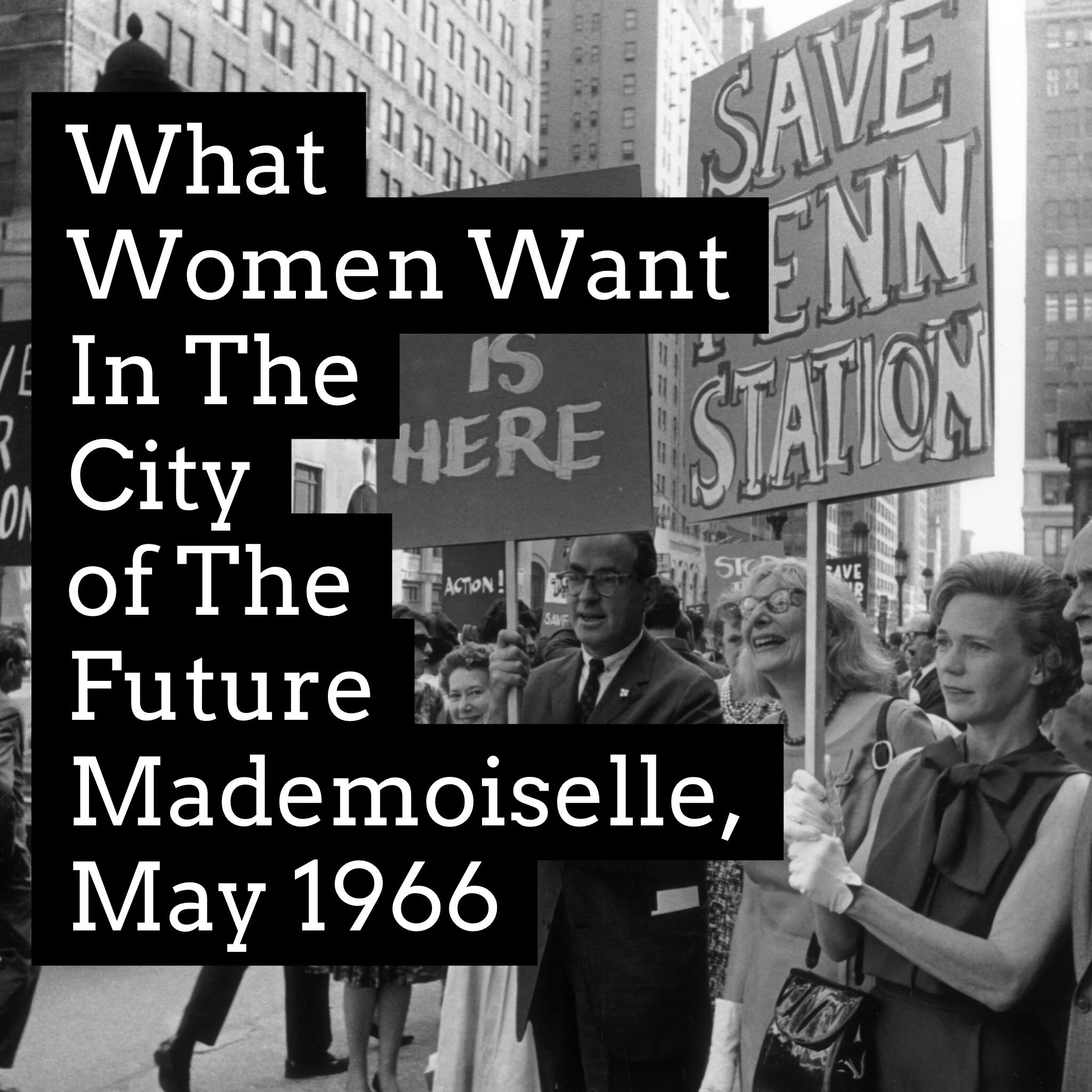

What Women Want In The City of The Future (Mademoiselle, May 1966)

What Women Want In The City Of The Future

Young Planners Tell Them What They Can Have And How To Get It

Originally published in Mademoiselle, May 1966

According to recent estimates, four out of every five Americans will be living in cities by the year 2000. The problem of city planning for increasing millions has about it the monstrous proportions, and the unseen hazards of an iceberg. Even the portion of it we can see, the reveals problems of air pollution, water scarcity, the stress of constant noise, the spectacle of slums. Public transportation, stores, restaurants, movie houses, are overcrowded. Apartments are scarce, rents are high. Movement is all but impossible. (If present trends continue, the rate of traffic movement during the January New York City transit strike will become the daily norm – by 1975.)

Just as the greater portion of an iceberg is invisible, planning for the urban future is, essentially, charting the unknown. Our assumptions are anchored in the present social and economic situation, current political procedures, contemporary measures for dealing with large groups of people in schools, hospitals, subways, and today’s means of distributing goods. With the shift in the population percentages (more people over 60, more under 25), the effect of automation (less satisfaction to be derived from work per se) and the prospect of increased prosperity (more leisure), the whole dynamics of the urban future may demand concepts different from any that mankind has so far devised.

Convinced of the importance of women’s role in the urban life of the future, both as citizens and as mothers, Professor Paul Lester Wiener recently invited an editor of MLLE and three other young women to share their views with five students of his city-planning course at Columbia University.

The participants included:

ANN, employed by a leading national monthly magazine as an editorial researcher in the financial field.

PAMELA, a young married woman living in a large housing project, working in social-service work through her parish church, expecting her second child.

RENA, a young woman attorney working for an organization to aid indigent people.

MAURY & JACK, whose background for their city-planning work is architecture

FRANCIS, an architect and instructor at Columbia

DAVID, a B.A. in history, who has chosen to work in the field of regional planning

JOHN, an Englishman who will specialize in urban design.

PROFESSOR WIENER, architect and city planner.

OUR EDITOR: What makes you want to live in a city rather than a suburb?

ANN: Your work is here, and you want to be as near as you can – not only to your work, but to the theatres, and to the financial district, if you’re in the type of work I am. And you have the conveniences you wouldn’t have outside the city.

MAURY: The proximity of everything: the activities that you want to take part in. Quantitatively,

the city has for me what I want. Qualitatively, it doesn’t, at present.

RENA: The people, a sense of anticipation in meeting new people, the quickness of ideas –

PAMELA: One has always the feeling that around the next corner something new may be lurking. In the suburbs, perhaps, this isn’t quite as true.

JOHN: I really resent the time that one has to spend in going to and from work if you live outside the city.

EDITOR: Then what is wrong with city living today? How can city living be improved?

ANN: As a single person in New York, I miss not being able to have a car. I used to live in Boston. It was very easy to have a car and to park it, and to get around. If you wanted to go and play golf or to go out to the ocean, you hopped in your car and you went. In New York City, you can go down to Penn Station and take a train out to Jones Beach, and you can go over to Central Park and go ice skating, but you’re constantly dependent on a taxi or a bus that doesn’t come, or a subway that’s dirty and dangerous. I am living where I am now, simply because I can walk to work. I don’t care what my neighbors are like, how far it is to the supermarket, or where the dry cleaner is, so long as I can walk to work and stay off that subway! I admit, it is an obsession. But if I were to be completely at peace, I would have my car and I would have a place to park it.

JOHN: The 200,000-plus cars that come into New York every day have priority over the fact that there are eight times that number of people living in Manhattan who can’t get to the waterfront. It’s ironical that here you are living on an island and you can’t even get to the damned water to walk along it! When you do get to it, it looks and smells unsanitary.

RENA: You talk about your compulsion about having to live near your work. Mine is air pollution. Don’t even open the window! Keep the window closed! Everything’s just covered with soot! And the fact that a child can’t go out in the street, can’t go down to the store after a certain hour because there is such a lack of communication between the elements in the city that he would be threatened, makes me shiver.

For instance, they’ve built a beautiful new playground near Grammercy Park and a friend of mine took her child to play there. Dope addicts were sitting on the slide, and there was a drunk in the sandbox. It was a very alarming thing, this little park open just about a week. It’s not that I even begrudge the derelicts who frequent these places. But until there’s some kind of a solution to that problem, the building of that playground is almost irrelevant.

PROF. WIENER: When we talk about improvements of city life, we have to be clear, first of all, what are the functions involved? They can be classified. First comes dwelling, then work, then recreation, education, and sports, and every other activity that recreates human energies.

Then we have circulation, which means everything, which means everything above and underground, including cars, cables, airplanes, subways, and sewers, and so on. The difficulty with our cities today is that those in power who plan for the cities deal largely on a piecemeal basis and do not realize that one decision is always dependent on the other. This playground seems to point up a moral problem, a problem of society more that one of city planning. The city planner is primarily concerned with the physical aspects of the city, in the hope that his physical designs will provide the background for a reasonably good life. But the morality of the people, and the fact of having derelicts and a terrible crime rate – this is something that even a good city plan could not really correct.

JACK: I think today we’re realizing the responsibilities that the planner-architect has, and that our society might more easily work toward the comprehensive planning that the Europeans seem to have undertaken; they have integrated social systems with economic systems, which we haven’t been able to do yet.

EDITOR: What do you mean by “integrating social systems with economic systems”?

JACK: Well, I mean integrating welfare, the poverty programs with urban-renewal programs. Instead of having piecemeal, individual agencies with their own programs, all this might be coordinated under one city-wide body.

JOHN: The difference between the European and the American approach is that in the States you are more interested in the technological functioning of the city, whereas in Europe, while it might be more backward, it is certainly producing an environment that is more humanely desirable. In Europe, we have a certain historical continuity, while, over here, all interest centers on providing technical efficiency in transportation, sewage and what not, and the people as individuals are forgotten.

EDITOR: Do you mean, for example, that poor people live with rich people – that neighborhoods are variegated in that way?

JOHN: I think the social systems are not quite so sliced as they are over here. But it’s really more that it’s just pleasant to live in a European city. I lived in London for three years. Compared to New York, you have ready access to the everyday things that you expect even in a smaller city, whereas here, you are in a tight bottleneck, and you have no feeling of being an individual; I am just overwhelmed here by the inhumanity –

In London, I lived within two miles of Piccadilly Circus. I was able to walk to work. I lived in a square where I could see green, and I had a pleasant outlook. Whereas now that I live within two miles of Times Square, I see a six-lane freeway; I see no trees at all; if I do see them, I cannot get to them. I cannot get to the waterfront – and everything’s much dirtier.

FRANCIS: One of the reasons Americans travel to Europe so much, and there is so much fascination with the Italian hill towns, the little sections of Paris, and so on, is that they physical form is a reflection of an integrated social environment. Any approach to city planning, any intelligent view of the city, must see the social-economic political forces as a matrix out of which evolves the physical form, and usually the planner has looked only at the physical aspects.

For example, Peter Rossi, a sociologist, has argued that all moves to the suburbs are made at the birth of the second child – simply because the city does not have enough physical containers for families exceeding one child. Louis Worth, another sociologist, wrote that most urban social contracts are segmental and, in a sense, predatory; he said that the smaller, more cohesive community in which there was a great deal of social interaction, in which somebody’s child could be watched, for example, by other mothers in the playground, this is a thing of the past because there are no forces of social control now. Urbanites are self-centered, selfish, predatory.

JOHN: You’re placing too much emphasis on the ability of the planner, who is essentially a physical planner, to control sociological conditions. In his own microclimate he can design a humanized element desirable to the family as a group, or perhaps to a neighborhood. But he can’t control sociological conditions. This is a moral issue and it requires education.

EDITOR: What will the new concept of city planning be?

JACK: Maybe a very tight city-planning department that deals with all phases of planning, and in doing so, doesn’t only create an ideal plan, but also works for some practical solution.

Because the concentrations will have to be so much greater in the future, we’re working toward what has been called the “megastructure” – that is, the great massing of structures in one place, which utilizes very, very efficient functioning of different elements. People will have to accept that we’re going to be living and working even closer together. What we are doing now in New York City, might be applied, say, to Springfield, Massachusetts, or even in the areas out West that can’t even conceive of this sort of living right now. A megastructure contains most of the living functions – work, recreation, shopping, eating, and basic everyday needs. In other words, you will not have to go, say, five blocks to get to a store; you will have to go maybe up two storeys or down three.

EDITOR: Megastructure seems to me a most inhuman word for quartier. This is what’s wrong with cities! Suddenly, you come along with a word like megastructure and the human being doesn’t understand you. Pammy, you live uptown on the West Side in an area that people are trying to upgrade – can the city be translated into human terms there?

PAMELA: My area is very interesting. I live in a project built by a speculative builder, Mr. Zeckendorf. A vast and inhuman filing cabinet is what I live in. But I also live on the upper edge of the West Side urban-renewal area, which is, I would say, a far more realistically planned project. It’s almost impossible for human beings to create any sort of lives for themselves in the project where I live. For example, we have vast quantities of very young people – young marrieds – and vast quantities of very old people. But the moment a family, has, as we’re about to have, two children – out! – because there isn’t a unit with more than two bedrooms. And this, to me, is absolutely inhuman. You’re forced to move to the suburbs – a prospect that makes me cringe.

DAVID: I think you’ve struck it, Pam: what attracts people toward the city. It’s a function of their marital status. People tend to gravitate toward various types of living environments as they progress in age and go through various periods in their life.

PROF. WIENER: Many people who have children have gone to the suburbs, and after the children had grown up, they returned to the city. Clearly, some city planning has to be developed to take care of these particular requirements. That is where one of the chief causes for discontent lies and, simultaneously, where the beginning of public support for planning can be mobilized.

DAVID: They’re now trying to make the city into a suburb. I think trying to make the city appeal to all age groups, to people of all opinions, of all backgrounds is complete folly. What alarms me is not that people who have two children leave the city. What alarms me is that single people no longer find the city attractive, and this is what the city is – or should be – for.

EDITOR: Well, is it only for young, single people? Isn’t it for people who have families, too?

DAVID: Younger people, and older people, and people that can afford it.

EDITOR: But did cities grow with just young single people and older people?

DAVID: No. This is not traditionally its background. But, with our modern technology, it is evolving into this.

EDITOR: In other words, a city is a luxury. But the young married women who are, after all, the life and soul of the future cities – if they move out of town with their children, the city dies. The old people who come back when their children are grown up, that isn’t a city any more. You want children playing in the streets. You want life.

FRANCIS: There’s been a very interesting book in this: Scott Greer, The Emerging City. He argues that there are two polar types: those who opt for careerism and the cosmopolitan life – the sophisticate and so on – as opposed to those who opt for familism and suburbia and the backyard swimming pool.

MAURY: But they had to opt for it because there was no variety offered in the same environment.

FRANCIS: That’s right, and I say this is because of the economic context. Nobody gave them the variety. Nobody gave them the two-bedroom apartment either.

PROF. WIENER: In New York or other very large cities, you have the problem of land values. This being a society of free enterprise – building is done for profit primarily – with or without subsidy. We don’t have enough land to give the public the advantages of the private house, the low-rise building. W ear compelled to have high-rise buildings to take care not only of the existing populations, but certainly the future ones.

Now, we can’t be sentimental as to what we consider is the desirable life. We can’t have the suburbs in the city. You can’t have a metropolitan area with all the advantages of New York on the one hand, without realizing that we have only a limited living space in which to accommodate the population. Land is being consumed very, very fast throughout the nation, and if we loosen up the pattern of cities as they are now – sometimes too dense – to provide more recreational facilities, parks, and playgrounds, that means we will have to put up higher buildings.

Now, I believe that it is possible to have a community life in high-rise buildings. Le Corbusier made an effort in Marseilles, and sentimental people said it would never do. The fact is, people were standing in line to get in. He had small rooms. He had a shopping street right in the building, and he had the playgrounds o the roof, where everybody could go. The laundries were in the basement. The aisles through which people passed were broad, not narrow corridors. Ad they got to know each other quite well.

JOHN: What fundamentally more beneficial system can you have than a high-rise apartment, like those in Marseilles, where everybody has something in common and you have facilities for providing day care or evening care for children? It’s just the rather naïve way this type of building is run in this country that precludes such opportunities.

FRANCIS: Well, it’s bigger than that. It’s the economic question. If you were to construct a similar unit here in New York, it would be a fantastically expensive structure. It would “out-Park” Park Avenue.

EDITOR: What about you young women? Wouldn’t you like to live in a place where there was, for example, a swimming pool, a tennis court within easy walking distance? And wouldn’t those of you who have children (or may have), like schools, amusement facilities, hospitals – or at least medical attention – within walking distance, so that you didn’t have to wheel your child to some other section of the city? Why would this be so difficult? It’s not in the realm of city planning, but it certainly is in the realm of scientific development to build more cheaply. Part of it, obviously is labor, but there ought to be ways to prefabricate these buildings.

JACK: Not enough money has been allotted in housing programs for research on pre-fabrication of structures that might contain all the facilities like tennis courts, swimming pools. The city planner might think not only about the two-plane system, where you have the ground level and the rooftop, but also about what happens in between. You might create intermediate levels where you wouldn’t have to go to the roof or to the ground level. It’s just a matter, again, of exploring and researching.

EDITOR: How do any of you feel about your neighbors? Would you consider interdependence on advantage in a community where people had different interests, different levels of income? Would you consider it possible, for example, for the wife of a subway changemaker to look after your children and for you to look after hers?

ANN: I would say it’s not possible within the existing setup, because they won’t live anywhere near each other.

PAMELA: I have two very distinct views of this West Side urban-renewal project (it’s a ten-block, north-south area, and extends from Central Park West to Amsterdam Avenue): one my own and the other through the eyes of the children – the lowest economic group children – with whom I work.. This project has been carefully planned by the city to include upper, middle, and lower income housing, all of varying types. But the children I work with see it as a lot of “swells,” a lot of rich people coming in to displace them, shoving them from one slum to another – since not enough low income units are being built to house those who had to move out. Can this kind of planning work in terms of the people who will live there?

We have renovated brownstones that will be lived in by many families. We also have some very fancy, very rich people who have come in and made real showplace houses in the area. We have schools and shopping facilities.

Now, this really is an attempt to create an artificial quartier in New York, and it’s the best thing I’ve heard of in city planning.

JOHN: There is a ten-storey building near Columbia University, in which there is an active organization that looks after children day and night, if need be. The mother will take off a day and look after three or four children; se thereby accumulates so many children-plus hours. She might get 40 hours to her credit, which is very nice and it doesn’t involve any money at all.

RENA: The life I lead during the day – seeing poor people on the very, very bottom of the social scale, and their problems – and then, a completely different segment of society at night in my private life makes it hard for me to imagine a quartier, a building that really encompasses these disparate elements of society. To conceive of an architectural concept that could unite them when the human element is missing, seems such an insurmountable problem.

JACK: I’ve been studying the Harlem antipoverty program. The most worthwhile project in Harlem right now is the 114th Street project, which incorporates community centers in the basement of renovated tenements so that the people do not have to go five blocks to a community center to organize. They have their adult education classes, their hobby shops, right in the basements along with the laundry.

What we’re trying to get away from is the massive housing project that destroys all human scale and values. The 114th Street project is a breakthrough of sorts to get at the scale of live in the Harlem area. It is incorporating small play areas immediately adjacent to the basements, so parents can watch the children. This particular project is a pilot program. The idea hasn’t really been attempted on any large scale. Something like 1,600 people are involved in this project, of whom 1,000 are children – a fantastic ratio!

RENA: There are several areas within New York, where I would be absolutely delighted to have any children of mine in a supervised community project with other children from the neighborhood.

JOHN: But you have historical background against you all the way through. You will never really have the integrated society you need in civilization. There’s always been a concentric ring of the wealthy at one time living right in the center, and the poor living outside by the wall, and if they could afford it, beyond the wall. You’re trying to have completely the reverse, but you’ll never have it.

MAURY: Why is this desirable? I don’t see –

PAMELA: Well, I look out my living room window and I see a block of complete slum housing from Central Park West to Manhattan Avenue and 100th Street. Across Manhattan Avenue, I see public housing, the Douglass Houses. I live in a definitely middle-class, middle-income project. We get along, I should say famously.

The Douglass Houses run a thoroughly integrated play group for very small children. It works like a charm, in fact. I live in this variegated neighborhood now, I’m content with it. I am committed to the work that I do, which involved, let’s face it, living with these people, because if you don’t, then they’d have no trust in you as an individual. I’d never look forward to moving to Park Avenue. No. I have this neighborhood. I’m content with it. It’s what I want.

RENA: Nor would I look forward to living in a neighborhood where I would be in a completely upper-income situation.

PAMELA: People who live in New York are a specialized breed. You wouldn’t find this working so well, perhaps, for somebody in the Middle West. But I think it is extremely desirable.

RENA: Don’t you find something distressing about living in an area, whether it’s a city or a suburb, that’s stratified as to age group? There’s something so unnatural about it and very unpleasant. Where are the people in their 30s and 40s? These people are in the full bloom of their lives, and they’re not here. I find communication with congenial people, who are 10, 15, 20 years older than I am, very pleasant. I have more than enough friends in my own age group, but the kick in dealing with someone who is speaking the same language, to whom you can look for some conception of your own life as you approach that age – this is a kind of integrated life.

DAVID: I look for companionship from people my own age. Maybe the city is becoming a place of stratified people. But if this is the case, then it may prove an attraction for us.

FRANCIS: There are still a few 30-year-olds around here, too.

JACK: The idea of not being able to communicate with a. group that’s ten years older isn’t a problem. In Manhattan, you have strictly oriented groups of professional society concentrated on finance and law and business and things of this sort. You can’t possibly hope to communicate completely on their level.

EDITOR: Would you consider the old as a part of integrated life? What would you think of larger living units that would contain not only yourself, your husband (or wife) and your children, but older relatives? Do you ever think in terms of a kind of miniature, collective family, where there’s always someone to look after the children? Because now we know that not only the help situation, but that of old people, is also acute.

ANN: Well, I don’t think this is practical for a young working person. It wouldn’t be desirable from our standpoint because you get a building that has mostly young tenants, where everyone is out between nine and five. They might rush in for an hour and go out again. It would impose a terrific loneliness on a person who wasn’t living this way. Perhaps planning can change this, but I don’t think it could be done.

EDITOR: You can’t see yourself as a young married woman with an elderly aunt living with you, looking after the baby?

ANN: I can’t. Perhaps someone else could.

RENA: I can’t either. I think there is something glorious about really not worrying about your child except when he’s a few minutes late for lunch and you know he’s just down the street. But there’s a bad side to that, too. Although I complain of the lack of communication between the elements in the city, I left a Midwestern city because I couldn’t bear the degree of intimacy, the unwanted concern of your neighbor for you. I found it stifling! I’m from Detroit, originally, the center of the city, but from a fairly homogenous community with nice big houses and shade trees, where, as children, we ran out on the street in the morning and our mothers didn’t worry about us until six o’clock at night, because there was no need to worry. And then we moved to a suburb. For people who live like that, New York with all of its problems is almost a relief, because that suburban friendship is something that I could very well do without.

EDITOR: To get back to the interests of unmarried people, Charles Abrams’ recent book on city planning said that the city should be a huge trystorium for young people. Considering the number of unmarried young men and young women in the city, he pointed out the few ways in which they can get to know each other.

ANN: Teenagers getting together, that’s what he’s talking about! I think adults in New York will meet the type of people they’re interested in meeting without a Charles Abrams telling them where to go.

EDITOR: How do you think they do this?

ANN: I would hesitate to generalize, but, for one thing, so many people have relatives here. Or you’re a native New Yorker, and if you’ve been to school here, you already have a group of friends. You’re not going to run off and join the Young Republicans simply because you think it might be fun addressing envelopes with some lawyer from Wall Street.

EDITOR: What about people who come from other cities?

FRANCIS: Yeah, you girls are in a definite category, but what about the out-of-town girl you is beginning as a secretary or something like that? Where can she meet somebody?

RENA: I think, Gentlemen, well-intentioned as you are, that it’s really beyond your scope!

EDITOR: The problem exists.

RENA: But people have interests, presumably. If they don’t, that’s their problem.

EDITOR: That’s true. But in so many European cities there is a promenade. Look at Venice. Everybody walks around the square in Venice.

RENA: Where I was in college, there was such a thing as a promenade, and I wouldn’t have been caught dead on it!

JOHN: Oh, really?

MAURY: Well, that shows you’re desperate!

FRANCIS: Take an insurance company or an ad agency where they have clerical help in droves. Where do these poor girls go?

ANN: They go to the Coke machine.

DAVID: You know what they find at the Coke machine? Other girls.

FRANCIS: Yeah, I agree.

DAVID: Just look at the number of opportunities furnished at colleges as opposed to some place like here.

MAURY: The metropolitan-mixer concept is only a manifestation of something which goes much deeper than that, unfortunately. In European cities, you’re talking about something completely different. We’ve already called it a more static society. I don’t think it’s static; we’re confusing the issue. Maybe it’s just a little old fashioned, a different stage of evolution.

FRANCIS: It goes back to the anonymity of the city. You know, Louis Worth’s concept of the segmental roles people have in the city, instead of seeing people as more or less whole persons. And I’m sure a girl would want to know what the guy is like before she meets him. She has to have a little more of the background.

EDITOR: Wouldn’t you agree that the possibility of meeting other people – I don’t mean dope addicts sitting on the slide – would be desirable in an American city?

RENA: I really don’t; no, even thinking in terms of a small university city, which is something in and of itself. I went from Ann Arbor to Barnard, which is quite a switch. In Ann Arbor there were just all kinds of opportunities to meet people at mixers and planned things; at Barnard there was nothing, and I preferred the Barnard situation because it’s more human – it’s more real. The idea of providing a mating ground is so horrendous!

JOHN: Now we’re getting into the mating department. We’ve been talking about sociological events in the central city; but the fact is you just go there from nine to five from Mondays to Fridays, and you go out to your suburban home, or you live on the outskirts. The place is no longer desirable just as a place to go. You have to have a specific purpose. The difference between an American city and a European city is that quite often you can go out there purely with the prospect of something unexpected.

ANN: Oh, there are unexpected things in New York.

JOHN: There are unexpected things in New York, but they are not necessarily desirable.

FRANCIS: I think the European versus the American city is arbitrary. I worked in Paris for a couple of years. It was the same situation that Ann describes. You meet people through interests rather than through an arbitrary chance.

EDITOR: What do you think a city is going to hold 25 years from now? What do you hope is going to happen?

ANN: No more air pollution – and if we got that out of the picture, a lot of other things would fall into place.

PAMELA: In the next 25 years, do we really come to grips with the problem of slums? It’s a propitious opportunity, we all agree. But do we continue our present policy of “slumification,” as urban renewal encroaches on the present slums, or just throw them out a little bit more in the other direction?

I think a lot about it, as I devoutly hope I will be involved in it. There are two widely divergent courses that the city may take. One is an increase of the existing stratification of the very rich and the very poor. And the other, if people are smart – city planners in particular – is the creation of more neighborhoods like the one in which I live.

Now, who lives in cities? People live in cities. We have to consider how to make the city a reasonable place to live – I speak as a mother not of any particular socioeconomic group, just as a mother, because this is equally true of the mothers of the children with whom I work. We need a form of housing unit within the scope of the average family that is a reasonable place in which to create a healthy family atmosphere.

Is it possible to make New York City, in particular, a place in which real people can live, or do we have to just forget about the while business and give it over to an economic industrial complex?

EDITOR: Gentlemen, what do you think you can do for a city? And what would you like to see done?

FRANCIS: It’s two different questions. What I can do is nothing. What I would like to see done is all these things –

MAURY: The city planner has to jump into an eternal triangle that right now doesn’t exist, or if it does exist, it’s not strong enough – the triangle between the public, the planner, and the politician. City officials, of course – being politically elected – don’t want to do anything that steps on the social toes, or steps on the economic toes. So it’s a matter of getting right to the source, and that’s the people, the electorate.

EDITOR: Granted the political problems – what do you think is the most important thing to be done?

FRANCIS: I’d say eliminating slums is the most important thing. Then air pollution. And we have to increase recreational facilities. But I do not think these are politically feasible objectives.

EDITOR: Transportation is, obviously, a city agony at the moment – can anything be done about that?

FRANCIS: Certainly, transportation can be improved drastically. It can be designed much better. But these solutions have to be politically palatable; people are going to be taxed, bond issues are going to be et, et cetera. We have to get political decision makers to support the physical solutions.

DAVID: Physical solutions include many innovations. When I say that I would like to see in the future a better movement within the city – I mean not only the political limits of Manhattan, but also the New York metropolitan area, and some suburbs, too. It’s going to require a restructuring of the traditional city’s central core, which has gotten awfully big; and a new set of nuclei outside this overgrown central core, to support a new transportation system; a new type of interaction between various city oriented activities – economic, cultural, and things of this nature.

EDITOR: Could the subways be not only cleaner but safer?

DAVID: It’s done in other cities, and there’s no reason why not here.

FRANCIS: Stockholm, for example, has a beautiful subway system. It’s clean, it’s fast, it’s efficient. It’s such a desirable situation that Ann would probably not want her car.

FRANCIS: It can be done, but it takes money and political implementation.

PROF. WIENER: The whole question of transportation should be further explored: mass transportation; the individual car; mass trucking during the daytime. I, personally, for instance, think that the roads being built are not efficient. The trucks traveling on them during the day clog up other traffic.

Make oversize trucks permissible in the city only between seven at night and eight in the morning. A small new type of warehousing would permit small trucks to make minor deliveries. Both labor unions and manufacturers would have to agree to absorb the extra cost of doing that. New construction of roads, streets, and parking areas is infinitely more costly than the extra hours involved. At the present time, we are subsidizing the automobile manufacturers at the expense of the public.

Mass public transportation has to be improved on a regional level. Then most people will be tempted to use mass transportation as against the private car – certainly within the city. Peripheral parking at the outside with very good connections with mass transportation on the inside is essential.

These very simple things can be accomplished without changing the political structure of our cities, through ordinances set by each city or by the region. The unfortunate thing is that we always wait until the disaster is upon us. Public opinion is not prepared and not knowledgeable enough to stand for these improvements at the right time, so we all suffer from this delay.

MAURY: It’s essential to get the man in the street to relate to this whole comprehensive plan. He feels completely apart from everything. It’s a matter of telling people exactly what their place is in this evolution, and making them realize that an evolution is inevitable. We’re in the midst of an evolution right now, but most people refuse to accept it. People have been brutalized because of their own apathy; because no one took an interest; because land was something to be bought and sold; because cramming more rentable floor space into a building, instead of setting it back on a plaza, was profitable. The speculator somehow moved in where there was no one else. There was no public opinion to stop it, no architect who had the backing to do something creative. There was a void. The speculator with a lot of money was there before we had realized what had happened.

ANN: The speculative builder isn’t mush concerned with the people.

MAURY: Well, but he is in a way. He is very responsive to people’s demands. The builder’s building isn’t an action; it’s a reaction to public demand. The speculative builder is providing what people want, or have been educated to want.

FRANCIS: There has to be a basic transformation of values, and I’m a little pessimistic. I think the housewife is conservative. As long as it’s the Great Society, everybody’s all for it, but the minute she realizes her husband is going to be taxed, or we’re going to have a bond issue to create a little public park in her neighborhood where her kids could play, as opposed to her own back yard in a suburb, and her own little plastic swimming pool for the kids, she would, I think, definitely prefer the private choice, not the public choice.

RENA: I would, any day, prefer an over-all kind of involvement to my own little heaven somewhere the size of a postage stamp, but I can tell you that those nice ladies out in the Midwest – and I mean the college graduates – they want their own picket fences and backyard swimming pools. They really love it! It’s great! The idea of exposing yourself to all kinds of danger and disease, and God knows whose children! And these ladies are of a liberal bent.

MAURY: Unfortunately, whenever you talk about something that’s common or shared, something that’s community property, you are talking about socialism, and this is contradictory to our basic American way of life. That’s why we all came here! Let’s face it. You know, way back in 1620 when they plunked their foot on that rock, they came here to get their own plot of land and nobody was going to tell them what to do with it, or which building to worship in. So we’re talking about a social evolution from “me-firstism” into “we-firstism.” A realization that in these cost-benefit analyses there are other things besides strictly economic considerations.

JOHN: Precisely, but here, in this country, you just have a complete monetary value. You have no idea of human values, cultural values.

The population explosion and World War II have forced us to produce masses and masses of housing. Now, we’ve come to a sudden realization that people are not living in the suburbs and the people who are going to the central city are not getting the values they want, so we have an opportunity to rethink – it’s the first time you know – with our urban renewal, and with the decay of the first city – from World War II bombing, for example – that we have had a chance to rethink.

You’re coming around to the point now where the Federal Government, or the state government, is inevitably going to have more power. It has to. You can no longer have, whether it be New York or any large city, the surrounding suburbs determining their own future. There have to be over-all regional plans concerning transportation, recreation, or water pollution.

I think the city itself is really on the rise, and the people realize its attributes. But you have to get rid of its disastrous characteristics.

RENA: The thing that would really give me peace of mind, 25 years hence, is some kind of community citizenship with my neighbors.

PROF WIENER: We have here a continuous migration – and integration – a society that, as our English friend pointed out, is not a stationary and stable one. This continually raises new problems of integrating many diverse races, cultures, and income groups not only in New York, but in Detroit and other concentrated areas. In more stable societies like Europe, the sociological problems are somewhat easier to deal with.

You have beyond that the integration of the total family. In other societies the maiden aunt and grandmother are the natural baby sitters, and they live more or less with the family. That is the desirable patter in the Near East and still is in most European countries. The young people have different expectations from their immigrant fathers or mothers, different educational levels. They do not see eye to eye on education and bringing up children.

In the Chinese colony here, you find a very low crime rate, and the children are no problem to the mothers or to the city. There are very few derelicts, dropouts, and all that, because the family is still a totality. We have broken down this family pattern, for better, for worse, and until we can re-establish it or change it entirely, the task of the city planner will be very difficult indeed, because we don’t know where this excess of individualism is going to take us.

JOHN: The city 25 years from now has to be an integration of all functions, of all people, of all classes, whether economic or racial or social. It’s inevitable.

FRANCIS: But the economists argue against this. They say the inevitable trend is toward the centralization of managerial functions in the city. We’re in an industrial society no. We’re not in the traditional preconceived society.

JOHN: It doesn’t matter whether it’s industrial growth or not; man has always been basically a gregarious animal, and he has a certain dependency on working and living in conglomerations. The traditional form of the cities as we’ve known them in the past, is a different kettle of fish. The fact is, there is a need for conglomerations. The city has a very vital function in providing them.

MAURY: It is not that the people are against planning; it’s just that resistance has become almost innate. For example, the very concept of eminent domain, most people think, involves the concept of creeping socialism. People of this country must come to acknowledge that there are problems, and there are ways to solve them, but there will have to be sacrifices before they can be solved. SO, before any city planning is implemented, we need a comprehensive public-education program. People must realize what is happening and relate it to their own experience.

ANN: There is no central voice for the city planner right now in New York, is there?

JACK: A group called ARCH (Architects’ Renewal Committee in Harlem, Inc.) is trying to educate the public right now. They’re instigating a program in the city schools next fall in the seventh and eighth grades, to instruct the children in planning, and this program will be expanded eventually to New Jersey, Connecticut, and other metropolitan areas. It’s a part of the poverty program’s adult education. Actually, the middle-income areas are less educated on planning than the lower-income areas.

PROF. WIENER: Young children in school should begin to understand the relationship of the individual to the community. Each child must learn regard for his neighbor, learn that there is a constant moral question involved. Our particular society is a little bit catch-as-catch-can in this respect: each man for himself. This goes all the way from the economics to walking dogs.

MAURY: It’s the planner’s job to give the citizen the economic picture. Show him what will happen. Paint the most hideous picture possible, because chances are it won’t be too far off. Then maybe you can begin to get public support.

PROF. WIENER: On the economic issue, I am an optimist. I believe in the ever-increasing productivity of the United States, and eventually we will have enough money for all the things that we need – if we don’t spend it in foolish directions. We need an articulate public, sparked by the women of the country, because they would be most affected by the benefits for their families. If the public is continually aware, and if the women care enough and are articulate enough – and understand enough of the totality of the problem – we can have the things we need.

EDITOR: What can young women do to effect their own destinies in these ways? How can they bring pressures to bear that will improve their lot?

FRANCIS: I think every woman should turn into a Jane Jacobs [the author of The Death and Life of Great American Cities, published in 1961]. This would be the ideal situation. I do not agree with most of her ideas, but I think she is an effective social force, and anybody dealing with Greenwich Village has to contend with her. The City Planning Commission, for instance, hesitates even to think about studying the Village because of her. If every woman became a Jane Jacobs, there’s nothing you couldn’t accomplish. You’d have the tennis courts, you would have less air pollution, you’d have two-bedroom apartments, you’d have cars, everything.

EDITOR: You are saying that women who are both knowledgeable in the field and politically active are essential?

FRANCIS: Precisely.

PROF. WIENER: I have been here since 1913, and observed the moral and ethical climate, the values that prevailed then, where the artist was nothing more than a bum and a poet was a derelict. We have now a new generation of people who are not primarily interested in the acquisition of money. Many young people today are completely devoted to improving values; they have very definite attitudes.

In literature, in music, in the arts, you see a complete renaissance – a reappreciation of these things. I believe that none of this would be possible unless there were mass interest on the part of the younger people. I think they will override this go-getting instinct that was apparently necessary to mobilize the country’s resources and bring it to economic fruition. Now that we have attained a degree of prosperity with the added advantage of the sciences and technology, I think we shall see most of the things that we have been discussing tonight come to pass.